i don’t keep a log. lists like these usually feel like an attempt to prove something, and i’m not sure how much i trust my own memory of what was actually useful. most of what i read is forgotten within weeks. still, i spent a significant amount of time sitting with these specific books this year. some were genuinely helpful; others were irritating or simply confirmed an existing suspicion. i’ve tried to write these notes without the usual performance of “intellectual growth.” there is no overarching theme here, just a collection of various arguments and observations that happened to cross my desk.

the story of philosophy: will durant

this was the last book i finished this year. it is a biographical approach to ideas, which usually makes for better reading than a dense textbook. durant is a congenial guide, but he is clearly humanizing these men to make them palatable. it’s a useful map of how one mind informs the next, from plato through to nietzsche, even if it feels a bit too tidy at times.

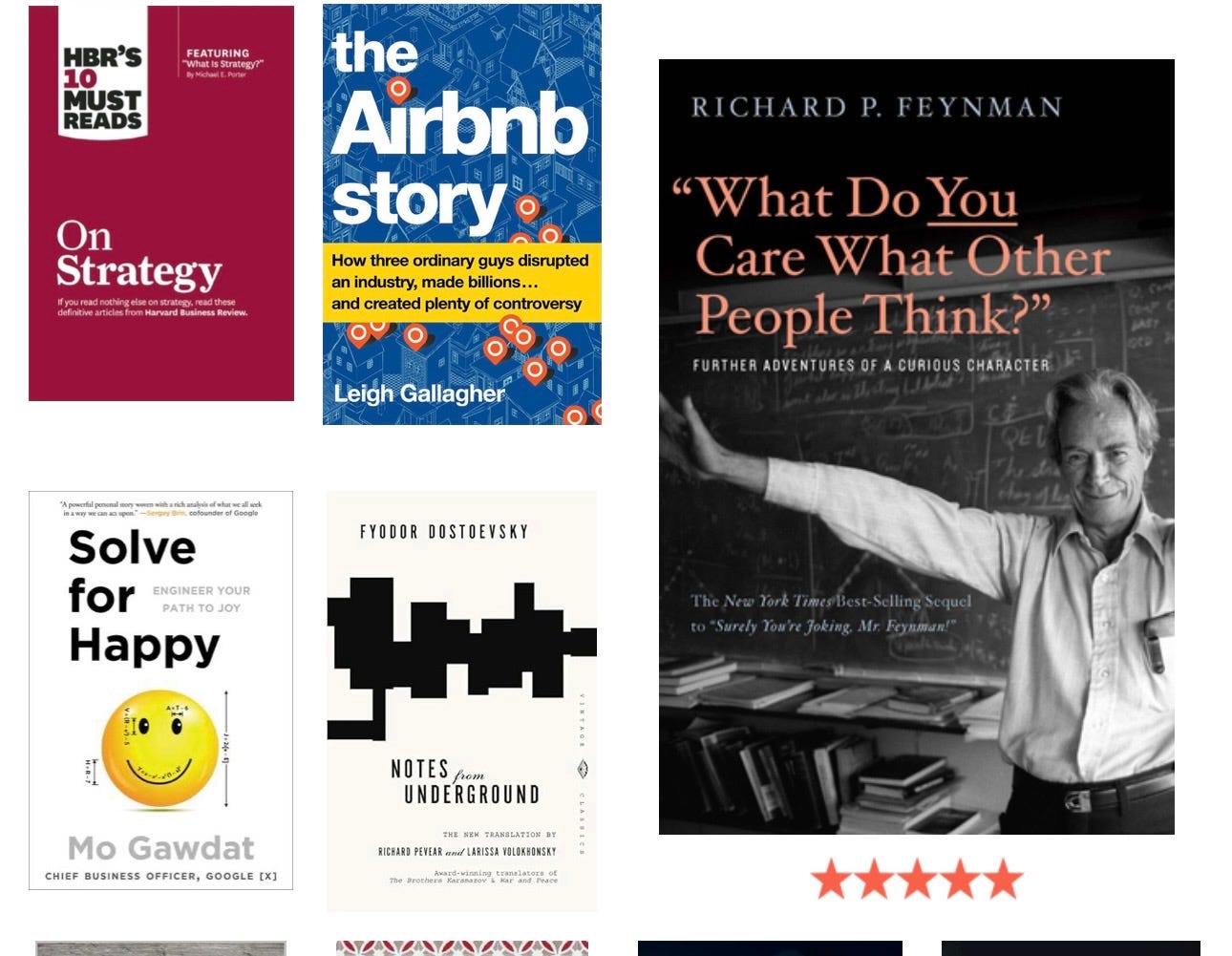

on strategy: various authors (hbr)

this collection is dry. it lacks the usual founder mythology and refuses to offer inspiration. it is mostly a sequence of trade-offs and structural constraints. it treats success as a matter of incentives rather than a moral outcome. i appreciated it for being boring in exactly the right way.

beyond good and evil: friedrich nietzsche

nietzsche spends a lot of time here attacking the “will to truth.” he’s suspicious of any philosopher who claims to be objective. it’s a jagged, aphoristic book that feels like a series of small explosions. i found his critique of “slave morality” more interesting as a psychological observation than as a moral prescription.

genealogy of morals: friedrich nietzsche

a deeper dive into how our concepts of “good” and “evil” actually formed. he argues they aren’t eternal truths but historical accidents born out of resentment. it’s a brutal way of looking at conscience. even if you don’t agree with his contempt for pity, it’s hard to ignore his point that our values often have very muddy origins.

the antichrist: friedrich nietzsche

incendiary and often unfair. it is difficult to read without feeling the weight of the attack, even when the arguments overshoot their mark. it is an uneven book, though the aggression feels honest.

ecce homo: friedrich nietzsche

nietzsche’s final work. the chapter titles—”why i am so wise,” “why i write such good books”—suggest a mind either losing its grip or simply abandoning all social deference. it is part autobiography, part polemic, and entirely strange. it’s a rare look at a thinker who is fully aware he is about to be misunderstood for a long time.

the man who knew infinity: robert kanigel

a biography of ramanujan, the indian mathematician who seemed to pull complex theorems out of nowhere. it focuses heavily on his relationship with g.h. hardy at cambridge. it’s a study in the friction between pure, raw intuition and the rigid demands of mathematical proof. ramanujan’s mind remains a mystery by the end, which is probably the only honest way to write about him.

a mathematician’s apology: g.h. hardy

hardy wrote this toward the end of his life when his creative powers were fading. it is a melancholy defense of “pure” mathematics. he argues that math is a creative art, like poetry, and that its “uselessness” is actually its greatest virtue because it cannot be easily co-opted for war. it’s a very proud, very lonely little book.

journey through genius: william dunham

dunham walks through twelve specific theorems chronologically. it’s a technical book, but it focuses on the personality of the proofs themselves. you see how archimedes, newton, and cantor each solved problems that seemed impossible for their time. it is less about history and more about the specific moments where a single mind broke through a structural limit.

perfume: the story of a murderer: patrick süskind

a novel about a man born with no scent of his own but an absolute sense of smell for everything else. the descriptions of 18th-century paris are revoltingly vivid. it’s a study in obsession and the total absence of human empathy. the ending is absurd, but the way süskind writes about the power of scent to bypass the rational mind feels accurate.

the peregrine: j.a. baker

obsessive nature writing. baker spent ten years following hawks in england, and the prose is so sharp it feels like it was written by the bird itself. he tries to strip away his own humanity to see the world as a predator does. it’s repetitive, claustrophobic, and entirely unique.

the republic: plato

moving through this slowly is the only way to do it. it’s unsettling to see how many of our “modern” debates about justice and governance were already being had in ancient greece. the arguments are cleaner here, stripped of two thousand years of secondary baggage. you realize we aren’t really coming up with new ideas; we’re just rephrasing the old ones.

theological-political treatise: baruch spinoza

this is a demanding book. spinoza’s attempt to separate religious authority from the state was a radical move at the time. he builds his argument brick by brick. it’s a foundational text for secularism, and reading it makes you realize how fragile those boundaries actually are.

the airbnb story: leigh gallagher

more interesting as a study in retrospective justification than as a business history. you can see the moments where the founders invented a narrative of “belonging” to cover what were originally survival-based pivots. it is a useful reminder that most legendary origins are polished long after the bank account is full.

solve for happy: mo gawdat

treating happiness as an engineering problem is a specific kind of category error. it is a logical book, but it avoids the question of why this kind of optimization is sought. it explains the mechanics while ignoring the premise. i found myself increasingly impatient with it.

notes from underground: fyodor dostoevsky

short and unpleasant. the narrator is spiteful and self-aware, though the awareness does nothing to change his behavior. it is a useful demonstration of how intelligence and resentment can occupy the same space without contradiction.

what do you care what other people think?: richard feynman

feynman had a genuine indifference toward authority. he wasn’t trying to be subversive; he simply didn’t care about social deference. his irreverence doesn’t feel like a pose, which makes it easier to read than most memoirs of its type.

letters from a stoic: seneca

stoicism often looks like a philosophy of endurance rather than one of inquiry. seneca is articulate, but the goal of total emotional withdrawal seems like a significant cost. i found the logic consistent but the project itself unappealing.

why i am an atheist: bhagat singh

written in a cell, yet the tone is sober. it doesn’t rely on strawman arguments. singh takes belief seriously, which makes his rejection of it feel more substantive than modern polemics.

the crowd: gustave le bon

blunt and dated. le bon is cynical about collective behavior, and while some of his claims are overstated, his description of how individuals vanish into a mass is difficult to dismiss. it leaves you feeling wary.

incompleteness: rebecca goldstein

a grounded look at gödel. it avoids the mysticism usually attached to his work. incompleteness is presented as a structural reality of logic rather than a cosmic mystery.

homo deus and nexus: yuval noah harari

harari is a better provocateur than a forecaster. his confidence in what comes next is usually the least persuasive part of his writing. i didn’t like nexus specifically—it felt like a collection of think-pieces i’d already read elsewhere.

the manipulated man: esther vilar

this was a strange read. vilar argues that men are the ones being manipulated through a system of domestic control. it is a total reversal of the usual gender narratives. much of it feels like a provocation intended to annoy as many people as possible, and it’s often quite funny in its bluntness. meh, but good for fun.

pitch anything: oren klaff

i didn’t like this. it treats human interaction as a series of “frame battles” and dominance displays. it feels like a manual for a very specific, very exhausting way of living. as a way of communicating with other people, it feels hollow.

the forgotten era: max siollun

a careful, corrective history. siollun focuses on the details that are often omitted from simplified versions of nigerian history. it is a grounding read that makes the present feel more complicated.

i’ll stop here. there is no real connective tissue between a manual on corporate strategy and a 19th-century novel about a misanthrope, other than the fact that they occupied the same shelf for a few months. i don't feel particularly changed by the year’s reading, but i am glad to have the noise of some of these books out of my head and the clarity of a few others settled in.